Mondongo & Nicolaus de Cusa (English)

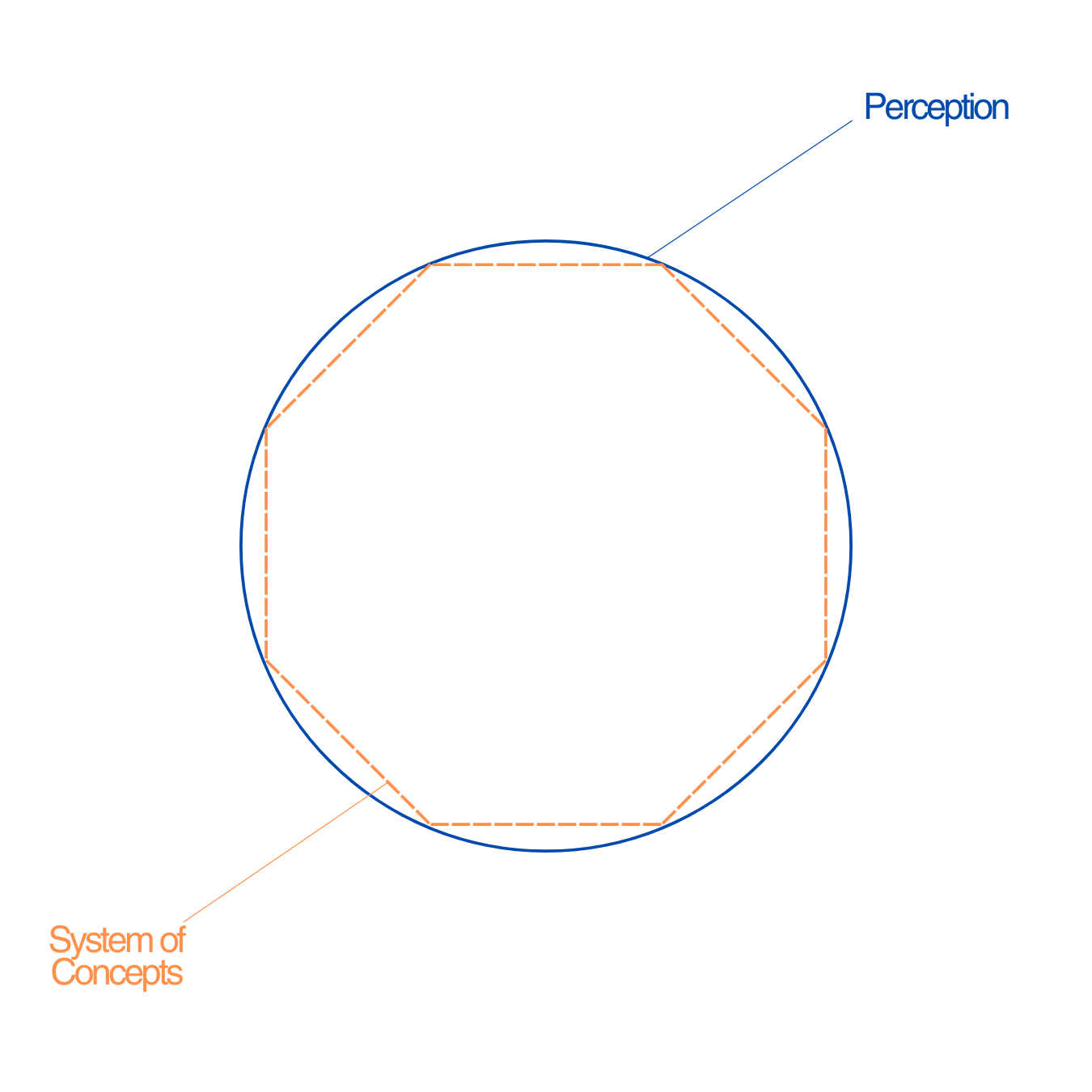

Suppose you have a triangle on your hands, and your task is to create a circle. Naturally, one starts by adding sides: the triangle becomes a square, then a pentagon, and so on until only up close you can distinguish the sides. From afar, it appears to be a circle. This is an illusion: the more sides you add, the farther away you move from the circle. The circle is composed by only one side.¹

The perfect circle is perception—boundless, infinite, with neither a beginning nor an end—a continuum. Meanwhile, the geometric shape with thousands of sides represents the structure of concepts we build, each side is one concept. It gives us the illusion of understanding the world around us by seemingly approaching the circle. No matter how hard we try (especially today), words, images, or a virtual reality model of a tree cannot replace the feeling of standing beneath one. However, it is through concepts that we typically navigate through life, they are necessary in our day-to-day. When there is a red light while driving, you need to understand the concept and stop if you don't want to crash. For that, we must recognize it as an element meant to communicate, not solely as an object of perception (aesthetic).

Art can be the circle; it can be pure perception. Evidence of this lies in the history of Modern Art and the great reduction it undergoes—moving from works “understood”through logic and concepts (e.g., David, The Distribution of the Eagles, 1810), to the merging of figure and background, and culminating in non-objectivity, i.e., paintings perceived with the senses, not with concepts (e.g., Reinhardt, Abstract Painting Blue, 1952).

That said, we recently went to see Mondongo’s Skulls and Baptistery. These works are the geometric shape with a thousand sides.

When you look at the Skulls, every crevice holds a concept to recognize and understand (or not): a philosopher, a movie, a character, a book, a logo, a painting, and many others. They are impressive because of the sheer number of elements and the detail (you can’t help but admire the level of work). It seems there is always something new to discover, something you haven’t seen before, but in reality, there isn’t—they are finite. Just like concepts, they fall short of showing reality. You must use logic, not perception, to appreciate these works. They seem to be a symptom or reflection of the times we live in. As Kevin Power writes, “the skulls appear to represent, rather, a certain version of the contemporary psyche.” From our perspective, they are one side of the coin; the other side is the search for the circle and the response to the history of modern art.

The Baptistery is a clear example of the thousand sides—3,276, to be precise (even when adding mirrors on the floor and ceiling to give the illusion of infinity you are getting driven further and further away from pure perception). All these blocks of color, segmented, categorized, ordered, and quantified, show us how we can reduce the infinite spectrum of colors in the world to numbers and letters. Now, when you step out of the Baptistery onto the balcony, how many colors can you see? Infinite.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” - William Blake

The more angles the inscribed polygon has, the more similar it is to the circle. However, even if the number of its angles is increased ad infinitum, the polygon never becomes equal [to the circle]… This is a passage found in On learned Ignorance (1439-40) by Nicolaus de Cusa.